I’ve been visiting Basel in northern Switzerland regularly for more than a decade. At first, like most visitors, my attention was drawn to the old town rising above the Rhine, anchored by the Münster and the ornate town hall; to the river itself, steady and unhurried; and, in winter, to the Christmas markets that briefly settle into historic squares and streets. Clean-lined modern architecture of glass and concrete sits comfortably alongside medieval buildings and grand townhouses, while public transport moves with quiet efficiency. Life feels ordered and understated here, confident without being showy. It’s a city that appears composed and carefully managed.

But familiarity changes the way you see a place. Over time, my visits began to stretch beyond the historic centre. I walked further, lingered longer, followed tram lines to their quieter ends and into the city’s industrial backbone of ports, rail yards, warehouses, and utility buildings. Gradually, the urban art environment began to catch my eye.

Basel’s relationship with art runs deep. Museums, galleries, and international art events are firmly embedded in the city’s identity, and contemporary art has a visible presence in public and institutional spaces. Large murals are often commissioned or at least tolerated, some remaining in place long enough to become familiar landmarks.

Within that context, street art and graffiti occupy a more ambiguous position. They are not overly encouraged, curated, or promoted, yet they exist alongside a culture that takes visual expression seriously. Large-scale works appear on warehouse walls, factory sites, and temporary developments, adding colour and narrative to spaces that would otherwise be purely functional.

Since first picking up an iPhone, my photography has been rooted in urban environments, focused on streets, alleys, and overlooked spaces. Working with a phone encouraged a way of seeing that is immediate and responsive, less about preparation and more about reacting to what’s already there, building a sense of place from fragments rather than grand scenes.

A desire to look more closely, to understand how urban art fits within a city so deeply shaped by culture and institutions eventually turned into a mini-project. Not to catalogue every wall or chase particular artists, but to spend time with the places where this work appears and ask why here, why now. Street art became both subject and guide, leading me through parts of Basel I might otherwise have passed through without really seeing.

In Basel, I've come to recognise and understand distinct areas of urban art...

Grand Hotel Les Trois Rois Bentley

I took this photo (below) way back in 2017. It's the first image that I captured of Graffiti art in Basel. The vehicle is a 2006 Bentley Arnage, a model usually associated with old-world luxury and understated elegance. It was used by Grand Hotel Les Trois Rois in the city centre to shuttle guests from the airport. The juxtaposition of a high-end limousine covered in neon-coloured graffiti was designed specifically to turn heads during Art Basel, the world's premier contemporary art fair. Approximately 40 students (aged 12 to 14) from the FG Basel private school were invited to spray the vehicle under the mentorship of renowned Swiss graffiti artist Thierry Furger, who guided the students in using spray paints and markers. The Purpose beyond being a "rolling art project," was tied to the hotel's support for children's charities, including a local children's cancer foundation.Though I’ve not seen it for some time, I believe the car is still used by the hotel.

I took this photo (below) way back in 2017. It's the first image that I captured of Graffiti art in Basel. The vehicle is a 2006 Bentley Arnage, a model usually associated with old-world luxury and understated elegance. It was used by Grand Hotel Les Trois Rois in the city centre to shuttle guests from the airport. The juxtaposition of a high-end limousine covered in neon-coloured graffiti was designed specifically to turn heads during Art Basel, the world's premier contemporary art fair. Approximately 40 students (aged 12 to 14) from the FG Basel private school were invited to spray the vehicle under the mentorship of renowned Swiss graffiti artist Thierry Furger, who guided the students in using spray paints and markers. The Purpose beyond being a "rolling art project," was tied to the hotel's support for children's charities, including a local children's cancer foundation.Though I’ve not seen it for some time, I believe the car is still used by the hotel.

Railway corridor east of Basel SBB

Often referred to simply as 'The Line', this stretch of wall beside main line railway tracks leading into the city's major train station has long been central to Basel’s graffiti history. Basel’s relationship with graffiti really took shape around 1985 when the long concrete walls were created. Almost as soon as it was finished it was painted, turning it into one of Europe’s most talked-about graffiti corridors. Basel was suddenly on the urban art map. Over time, it has developed into a continuously repainted surface, layered by successive generations of writers.

Often referred to simply as 'The Line', this stretch of wall beside main line railway tracks leading into the city's major train station has long been central to Basel’s graffiti history. Basel’s relationship with graffiti really took shape around 1985 when the long concrete walls were created. Almost as soon as it was finished it was painted, turning it into one of Europe’s most talked-about graffiti corridors. Basel was suddenly on the urban art map. Over time, it has developed into a continuously repainted surface, layered by successive generations of writers.

What remains today is less about individual works than accumulated presence. A record of repetition, erasure, and renewal compressed into a single linear space. For a photographer, the interest lies in that continuity. The Line isn’t a destination or a finished gallery. It’s a place where Basel’s underground visual culture has surfaced again and again.

Bell Site Mural

If visitors arriving in Basel by rail are welcomed by the graffiti of the Line, those arriving by air are greeted by something very different. Less than a mile from EuroAirport Basel-Mulhouse-Freiburg, close to the French border, the Bell site carries the largest street art mural in Switzerland. Created in 2020 as part of the Change of Colours event, more than thirty international artists covered around 1,700 square metres of wall surrounding the Bell meat-processing site. It’s an unmissable first impression, industrial in scale and setting, turning a working complex into a vast, outward-facing canvas.

If visitors arriving in Basel by rail are welcomed by the graffiti of the Line, those arriving by air are greeted by something very different. Less than a mile from EuroAirport Basel-Mulhouse-Freiburg, close to the French border, the Bell site carries the largest street art mural in Switzerland. Created in 2020 as part of the Change of Colours event, more than thirty international artists covered around 1,700 square metres of wall surrounding the Bell meat-processing site. It’s an unmissable first impression, industrial in scale and setting, turning a working complex into a vast, outward-facing canvas.

The wall is dominated by a large, three-part mural, bold and unapologetic against the industrial backdrop. On the left, Basel-based artist BustArt delivers a vibrant piece built from pop colour and cartoon-inflected forms. At the centre, the UK's Mr. Cenz takes control of the surface with a stunning portrait, the face surrounded by flowing, almost cosmic shapes. On the right, Chromeo and Bane, Swiss artists known for their photorealistic, three-dimensional style, close the sequence with a sharply rendered spray can wrapped in flowers. Different styles, different voices, but read together, the wall holds as a single, continuous statement.

City Murals

Tucked into a handful of city centre streets, contemporary street art slips quietly into the old town fabric, woven between medieval stone and everyday life. Three streets in particular, Gerbergässlein, Steinenbachgässlein, and Rosshofgasse, form a compact triangle of murals right in the heart of the city.

Tucked into a handful of city centre streets, contemporary street art slips quietly into the old town fabric, woven between medieval stone and everyday life. Three streets in particular, Gerbergässlein, Steinenbachgässlein, and Rosshofgasse, form a compact triangle of murals right in the heart of the city.

The Rock and Roll Wall of Fame (above) is the city’s most photographed wall. It sits in Gerbergässlein and is commissioned by the L'Unique rock bar opposite. It’s frequently updated, mixing classic legends with more contemporary figures, and has become a firm tourist favourite, a celebration of music culture embedded directly into the fabric of the old town. Art4000 is credited.

Steinenbachgässlein (above) is characterised by a long, continuous painted wall rather than a single, isolated mural. The artwork runs along the lower level of the street, applied directly to the building façades and wrapping around doors, windows, vents, shutters, pipes, and service panels. It reads as one extended surface made up of multiple connected sections.

The most prominent elements are large, 'History of Science' portraits including Albert Einstein, Nikola Tesla, and Leonardo da Vinci, each clearly labelled by name and dates, with references to science, engineering, and art integrated into the surrounding imagery. These portraits sit alongside illustrative and graphic elements including mechanical motifs, animals, and fantasy figures. Art4000 is again credited.

On the opposite side of the street, the imagery shifts to a more abstract, architectural style. Simplified cityscapes are painted in bright, vivid blocks of colour that run along the lower level of the façades, forming a continuous band that follows the line of the street rather than presenting a single focal image. Artist unknown.

Rosshofgasse (above). Tucked away in a narrow street, in the middle of Basel's old town, is a landmark mural by the British collective The London Police, a British artist collective founded in 1998 by Chaz Barrisson and Bob Gibson. Created during Art Basel 2015, Small cartoon astronauts circle a reclining female figure, who is based on local celebrity and burlesque artist Zoe Scarlett. It’s playful, surreal, and gently humorous.

Sommercasino

Built in the 1820s, Sommercasino Basel began life as a place for polite gatherings and summer socials. At the time, the word casino did not mean gambling, it meant a place to meet. Music, conversation, dancing, food and drink. A social hub. The Sommer part was literal. Set just outside Basel’s old city walls, it offered a seasonal escape, somewhere to spend long summer evenings away from the dense streets of the old town.

Built in the 1820s, Sommercasino Basel began life as a place for polite gatherings and summer socials. At the time, the word casino did not mean gambling, it meant a place to meet. Music, conversation, dancing, food and drink. A social hub. The Sommer part was literal. Set just outside Basel’s old city walls, it offered a seasonal escape, somewhere to spend long summer evenings away from the dense streets of the old town.

Over time, the building absorbed the city’s changing moods. During the Second World War it was used as a refuge and community space. In 1959, it became Switzerland’s first official youth house, a shift that reshaped its identity. By the 1980s it was central to youth culture. Gigs, club nights, DIY events, first bands, first nights out. For generations of Basel residents, it is tied to formative memories.

As the city tightened its stance on illegal spraying, the Sommercasino took on another role. Already established as a youth centre, it became a legal sanctuary for graffiti. A Hall of Fame in the graffiti sense. A place where artists could paint openly, experiment, fail, improve, and return without fear.

The walls follow their own rules. Nothing is permanent. Large pieces may last months. Smaller throw-ups can vanish in days. That turnover is intentional. The building reflects the city’s current energy rather than preserving a fixed past. It also works as a training ground. Younger writers watch experienced hands at work, learning letter structure, flow, and the urban calligraphy that has made Basel artists internationally respected. Knowledge passed wall to wall, not classroom to classroom. There is a clear sense of respect and hierarchy. In graffiti culture, you paint over work only if what you are putting up is equal or better. That makes the memorial to legendary street artist Robi the Dog unusual. The portrait by Gimix (below) has remained untouched since 2016. That kind of longevity signals deep respect within the community.

Today, the Sommercasino stands out precisely because it does not blend in. Its façades are layered with graffiti and street art, constantly changing and unapologetically visible. Inside, it continues as a cultural venue for concerts, parties, workshops, performances, and community-led projects. Social. Noisy. Imperfect.

Nineteenth-century high society architecture carrying the marks of contemporary underground culture. Not preserved. Not sanitised. Just allowed to exist.

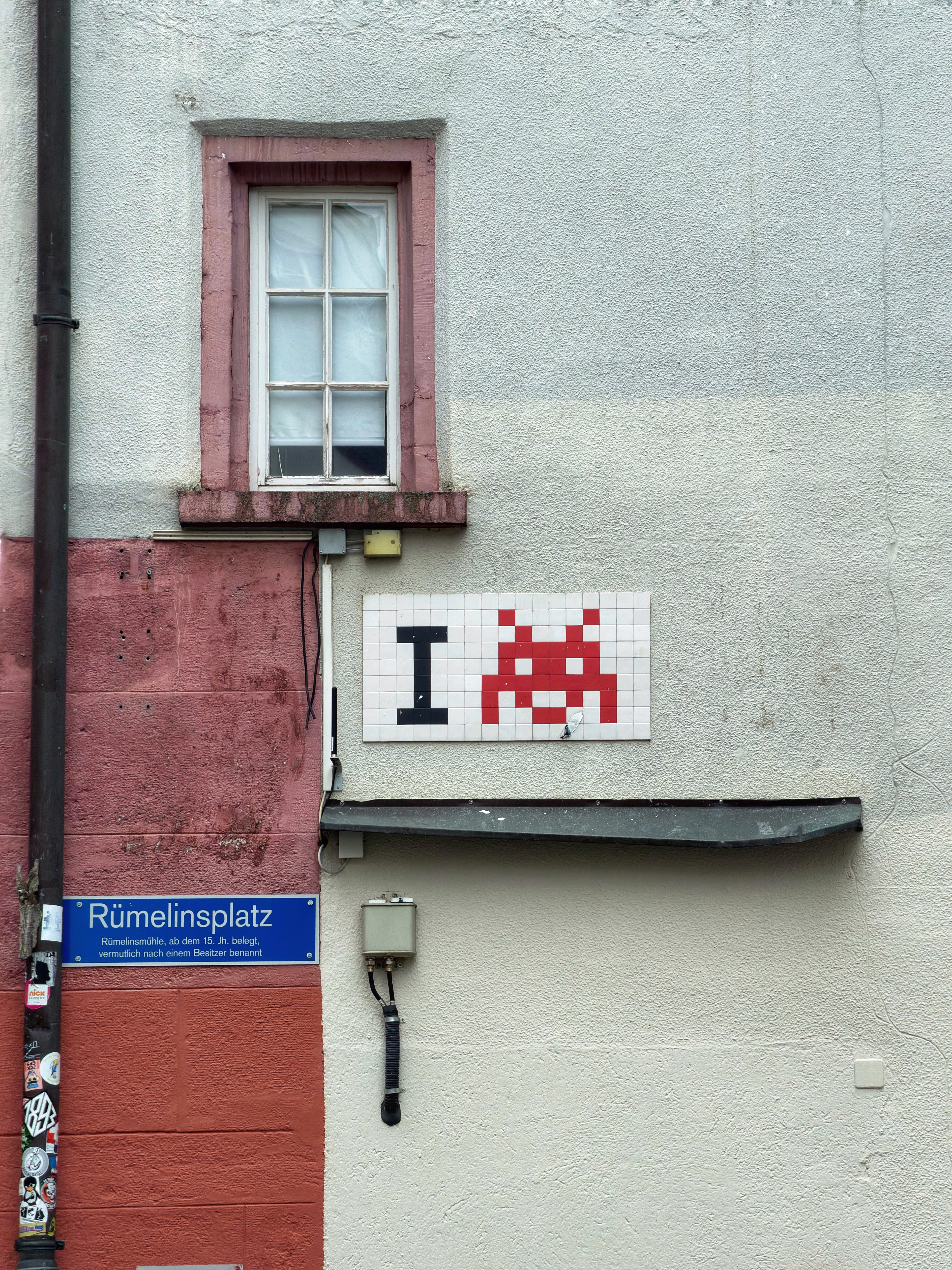

Space Invaders

For over two decades, a masked Frenchman known only as Invader has been turning cities around the globe into a living arcade. By cementing ceramic tile mosaics of pixelated characters inspired by the 1978 arcade game Space Invaders onto urban walls.He began in Paris in 1996. Since then, the invasion has expanded. More than 4,000 mosaics. Nearly 100 cities. Every inhabited continent.

For over two decades, a masked Frenchman known only as Invader has been turning cities around the globe into a living arcade. By cementing ceramic tile mosaics of pixelated characters inspired by the 1978 arcade game Space Invaders onto urban walls.He began in Paris in 1996. Since then, the invasion has expanded. More than 4,000 mosaics. Nearly 100 cities. Every inhabited continent.

And the reach goes far beyond city walls. His work has appeared:

Underwater — on the ocean floor near Cancún

At altitude — over 4,000 metres above sea level in Potosí, Bolivia

Basel has its own chapter in the story. There are currently 25 Invaders scattered across the city, installed first around 2013, then again in 2019. The giant Invader on Clarastrasse (above) is the standout. Big, bold, impossible to ignore. Ceramic tiles are used because they echo the look of early 8-bit pixels and they also last. Unlike paint, tiles resist weather, cleaning, and time itself, giving the work a feel of permanence.

If you’re inclined to hunt them down, the project is gamified through the official FlashInvaders app. It turns wandering the city into a kind of high-tech scavenger hunt: spot a mosaic in the wild, frame it with your phone, and “flash” it. GPS and image recognition confirm the find, and you’re awarded points, anywhere from 10 to 100, depending on the size of the piece, its complexity, and how awkward or hidden the location is. Those points feed into a global leaderboard, gently nudging exploration into competition.

Rheinhafen Kleinhüningen

If the old town is Basel’s public face, this area is its backbone, the city’s working edge. This is the port district, where river, rail and road are stitched together by industry and transit. Rail yards, container stacks, boats and goods trains sliding through without ceremony. Everything here is functional first, aesthetic second, which is exactly why it works so well photographically.

If the old town is Basel’s public face, this area is its backbone, the city’s working edge. This is the port district, where river, rail and road are stitched together by industry and transit. Rail yards, container stacks, boats and goods trains sliding through without ceremony. Everything here is functional first, aesthetic second, which is exactly why it works so well photographically.

The surfaces do the talking. Steel wagons layered with paint, rust blooming through older tags, fresh pieces running alongside decades-old marks. Graffiti isn’t framed or curated here, it’s mobile, transient, constantly overwritten. Trains arrive already carrying history from elsewhere, then leave again, taking fresh marks with them. Nothing stays still for long.

Light behaves differently too. Wide skies, hard shadows, reflections off metal. The rhythm is slower between trains, then suddenly loud and kinetic when a freight line rolls through. Fences, warning signs, ballast, cables, visual clutter becomes structure if you let it. Shoot low, shoot long, or just wait. Something always passes.

Container bars are one of the few places in Kleinhüningen where the public is invited into the working landscape. Built from repurposed shipping containers, surrounded by cranes, rail lines, stacked freight and the slow movement of the Rhine. Moored vessels tare also turned into seasonal bars and are a familiar sight along the Rhine in Basel. There’s no attempt to soften the setting. The bars lean into it. Rust, steel, warning signs and raw graffiti become part of the atmosphere.

Dreispitz

A former freight and logistics district on the edge of Basel, built to store and move things. Warehouses, long sheds, rail spurs, service roads. Functional architecture, spread wide and flat, designed for efficiency, not charm.

A former freight and logistics district on the edge of Basel, built to store and move things. Warehouses, long sheds, rail spurs, service roads. Functional architecture, spread wide and flat, designed for efficiency, not charm.

As freight activity slowed, some buildings stayed active, others slipped into partial occupation. Surfaces became available, artists arrived, the bare concrete walls became canvases. Since 2021, large sections of Dreispitz have opened up for street art, with selected walls formally handed over to artists. International names were invited, including Greg Lamarche from New York (above) and the result is a mix of spontaneous graffiti and carefully executed murals, running side by side.

Dreispitz today is a place in transition, the art has transformed it into a vibrant open-air gallery, featuring high quality urban art and murals on industrial buildings.Cultural institutions, studios, offices and housing move in carefully, without fully erasing what came before. Industrial function hasn’t vanished; it coexists.

My favourite piece in Dreispitz (below), is by Hendrik Beikirch, the German artist also known as ECB. He’s internationally recognised for his large-scale, black-and-white portraits, but it’s not just the technical skill that pulls me in. It’s the choice of subject.

This mural depicts Mario, a local warehouse worker. Before painting it, Beikirch spent time studying the faces of people who worked in the area, looking for someone whose face carried a story. Mario, a warehouse worker, was the one that stayed with him.

Beikirch describes his approach as documentary portraiture. He doesn’t paint celebrities or symbols. He paints ordinary people with a magnetic presence, faces shaped by time, work, and lived experience. There’s no drama added, no narrative forced. The story is already there.Set against the concrete and utility buildings of Dreispitz, the portrait feels exactly where it should be. Quiet, solid, human. It’s one of the most iconic works in the area’s evolving open-air gallery, and the kind of piece you don’t just look at, you return to.

Vogel Gryff, Rheingasse mural

This striking mural (below) depicts the three legendary figures of the Vogel Gryff. The Vogel Gryff is a historic, annual (Jan 13 or later) folk festival in Kleinbasel, Switzerland, featuring three symbolic figures—the Griffin (Vogel Gryff), Wild Man (Wild Maa), and Lion (Leu), parading and dancing to honour local traditions and, specifically, the Kleinbasel community. The artist is Guido Zitti, well-known in Basel, and his work often captures the vibrant, slightly mischievous spirit of the city's folk traditions.

This striking mural (below) depicts the three legendary figures of the Vogel Gryff. The Vogel Gryff is a historic, annual (Jan 13 or later) folk festival in Kleinbasel, Switzerland, featuring three symbolic figures—the Griffin (Vogel Gryff), Wild Man (Wild Maa), and Lion (Leu), parading and dancing to honour local traditions and, specifically, the Kleinbasel community. The artist is Guido Zitti, well-known in Basel, and his work often captures the vibrant, slightly mischievous spirit of the city's folk traditions.

Binningen, Dorenbach

I first noticed this stretch while travelling into the city on the 10 and 17 trams. Step off at Dorenbach and you’re standing right above the Birsig River. From there, the path follows the water downstream toward the Basel Zoo, slipping beneath an underpass where the walls start to come alive.

I first noticed this stretch while travelling into the city on the 10 and 17 trams. Step off at Dorenbach and you’re standing right above the Birsig River. From there, the path follows the water downstream toward the Basel Zoo, slipping beneath an underpass where the walls start to come alive.

This area is a frequent spot for high-quality "wildstyle" lettering by local crews. Because it’s a semi-legal space, the art changes more frequently than the larger murals downtown. The standout artwork is 'Ninja' (above), created by the artist Niro, a striking, high-contrast portrait that makes great use of the concrete wall's texture.

Steinenvorstadt

The final artwork in this post is a full-building mural (below) facing the Heuwaage Viaduct, overlooking one of Basel’s busiest intersections and the train and tram lines that run toward the Zoo and Basel SBB. The work spans the entire facade of the Steinentor building and is an striking sunset scene over the banks of the Rhine.

The final artwork in this post is a full-building mural (below) facing the Heuwaage Viaduct, overlooking one of Basel’s busiest intersections and the train and tram lines that run toward the Zoo and Basel SBB. The work spans the entire facade of the Steinentor building and is an striking sunset scene over the banks of the Rhine.

This is a temporary installation. The building is scheduled for demolition to make way for a new high-rise. Behind the project is the artist collective ÜBR.

Basel’s urban art shows itself best where the city gets worn in. Along rail lines, underpasses, service roads, the backs of buildings that carry the weight of everyday use. Photographing here means slowing down and looking harder, noticing what most people dismiss or step around. The iPhone fits this way of working. It’s small, unobtrusive, always there, letting you respond quickly without turning the moment into a performance. These pieces of art aren’t merely decoration, they’re the result of time, risk, intent, and people committed enough to leave something behind. Walk enough, linger long, and the walls speak for themselves.