Four weeks on the road. Beaches, cities, backroads. Morning fog, blazing sun, golden hour haze — and sudden thunderstorms that blew the day apart.

If there was ever a time to explore the versatility of mobile photography, this was it.

Different places, different light, different styles—street, landscape, documentary. I had time to experiment and explore possibilities.

I run workshops and present to camera clubs. People look to me for answers.

What app should I use for street?

How do I get the film-look?

Which manual app gives you better quality?

Should I use a grip?

How do I get the film-look?

Which manual app gives you better quality?

Should I use a grip?

And I get it—mobile photography has grown up. There’s a flood of tools out there promising more control, better dynamic range, film looks, DSLR-like handling. It's easy to think you’re missing out if you’re just using the default camera.

The YouTube photo influencers tell us so. Titles in bold: “Turn Your Phone Into a DSLR!” or “Why You’re Shooting Wrong.”

You know the type.

Backwards baseball cap. Maybe a woolly beanie worn indoors. Calls you Cuz, Bro, or Dude while asking "What’s up?"

Cue the slow-mo close-up: fingers loading film into the back of a Leica like it's a sacred ritual. A moody shot of him/her walking alone. Lo-fi beats humming underneath.

You're two minutes in before the sit down — minimalist desk, soft side-lighting, dead-eye stare.

Then it drops:

"The iPhone? Nah. Smartphone shots all look the same. You’re not capturing a moment — you’re watching Apple fabricate one. Too sharp. Too smooth. Too HDR."

And then the kicker:

"Hit the link for 20% off my Lightroom presets, buy the app, follow the workflow, click the affiliate link below. — The real cinematic film look your smartphone deserves."

Yeah, right, because nothing screams authenticity like digital filters simulating analogue truth.

And you're just sitting there like —

“Okay… I just wanted to take better photos of my dog.”

Truth? Your phone’s not going to become a DSLR. It’s still a phone — a small sensor, baked-in processing, AI sharpening your eyelashes before you’ve hit the shutter. And that’s fine. It’s why we use them. Fast. Light. Always with you.

The magic isn’t in the app or the lens simulation. It’s in you — where you point it, when you press it, and what you choose to keep.

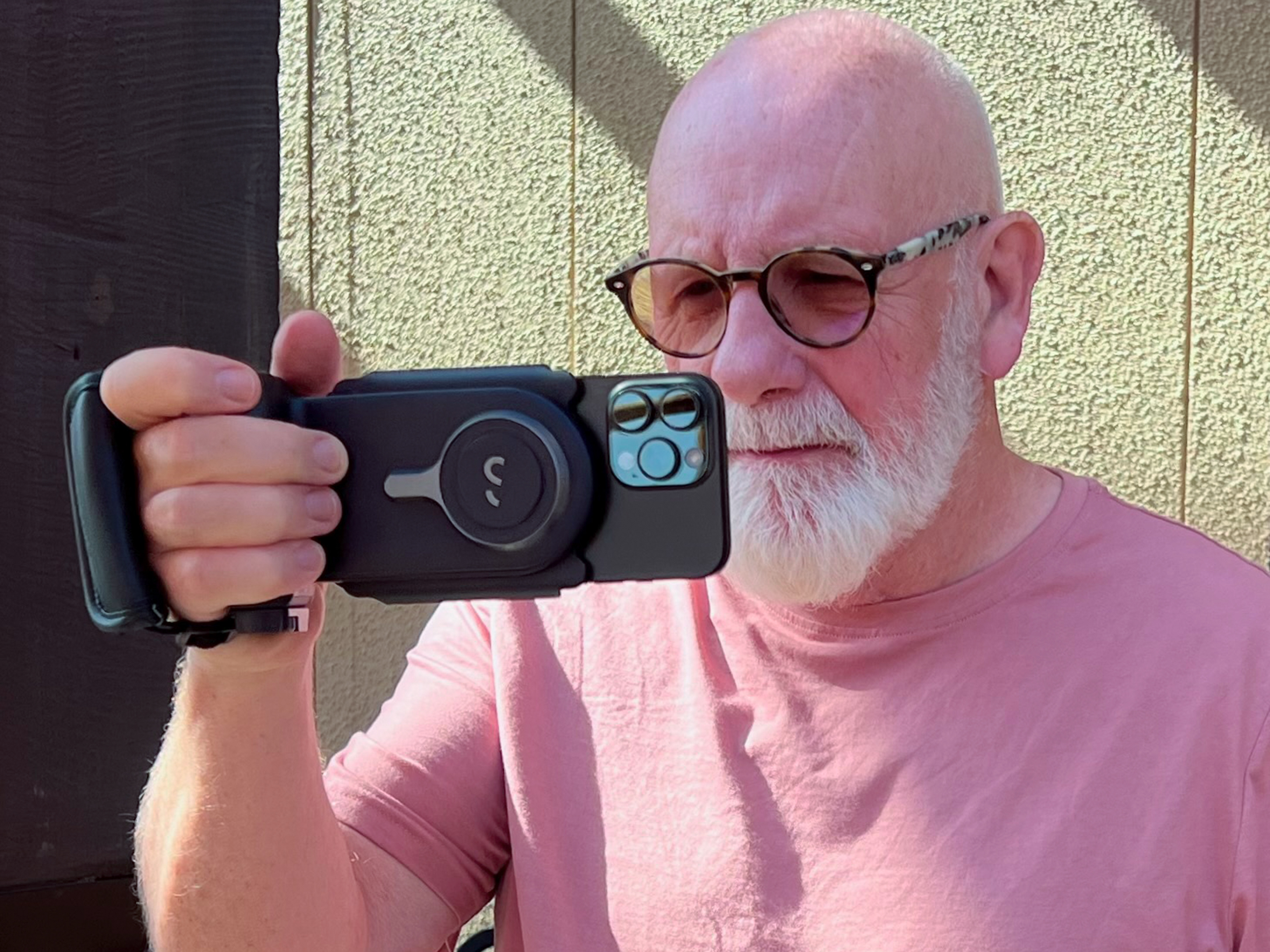

I use iPhones for photography because I love what they can do—and I share my experience and advice based on thirteen years of shooting with them. But if I don’t test things, I don’t have an opinion worth offering. So...ShiftCam SmartGrip

I get a lot of questions about grip.

Some people struggle with holding the phone steady, especially one-handed. Others say they miss the feel of a “real” camera in their hand—that familiar weight, that satisfying click of a shutter. They want something that bridges the gap between smartphone and DSLR.

So I gave the ShiftCam SmartGrip a try.

It’s well made. Feels solid. Bluetooth shutter button, tripod thread, cold shoe—all the right promises. And in the right conditions—indoors, slower-paced shooting, mild temperatures—it performs fine.

But out on the Florida streets, it was too much.

It added bulk. Drew attention. You lose case compatibility, which immediately made me nervous. One night back at the hotel, I bumped the grip while setting it down on the bedside table. The iPhone popped loose. Slid right out. Luckily, it landed on the bed. No damage done—but if that had happened on the street, it would’ve been game over. Possibly works with a dedicated ShiftCam case but that's more expense.

So I spent half the time worrying the phone would get knocked and slip, the other half fielding questions from strangers: "Hey, what kind of camera is that?”

And the shutter button? Some noticeable lag. Enough to miss shots I would’ve nailed without it (see top image). Additionally it is not fully compatible with all third-party apps.

In the middle of a street scene, these are the last things you want.

The SmartGrip might suit some people. It answers a question that gets asked often. But for me, it added friction—physical and mental. It broke the flow.

It made the phone feel like something it’s not.

Mobile photography works because it’s fast, discreet, always ready. When you start bolting things on, you risk losing what makes it great.

By the time I got home, the Amazon return window had closed.£126 lesson: for me, the phone’s already good to hold. Adding more doesn’t always help.

Testing Apps

I've always said: stick with the native camera until it lets you down. Only reach for third-party apps when the default truly can't deliver.

A good example? I use third-party long exposure apps because the built-in Camera app only offers long exposure through Live Photos, which has limitations.

I regularly test out apps to understand how they perform and what they add. And I get asked about them a lot, so I want my impressions to be based on real use, not just screenshots and marketing blurb.

Halide

I've used Halide on and off for years. Beautifully designed, packed with pro-level features, clearly built by people who care about photography. Gives manual control over everything — ISO, shutter, focus, white balance—and lets you shoot in RAW, ProRAW, HEIC, or JPEG. It's for those who want to take the training wheels off.

I've used Halide on and off for years. Beautifully designed, packed with pro-level features, clearly built by people who care about photography. Gives manual control over everything — ISO, shutter, focus, white balance—and lets you shoot in RAW, ProRAW, HEIC, or JPEG. It's for those who want to take the training wheels off.

I might be swimming against the current here, but I don't get along with Halide's Zero-Processing mode. It's one of the app's big selling points, a purist's dream. No Apple processing pipeline, no tone curve, no sharpening, no colour correction. Just the raw sensor data, straight into a ProRAW file. Flat. Neutral. Untouched.

And yes, it delivers.

But here's the thing: you've got to know what you're doing. You've got to want to work for it. Every shot becomes a project. Exposure, white balance—if you mess it up, it's yours to fix. There's no guardrail.

This isn't why I got into mobile photography.

Truth is, Apple's default ProRAW already gives you plenty to work with. You get flexibility, room to recover highlights, clean colour—but without everything stripped bare. Which reduces editing time, and that matters when you're on the move.

Less time editing. More time shooting. Essential when you're living out of a suitcase, and the next town is just one short sleep away.

Project Indigo

I've been keen to road-test Project Indigo, a free app developed by Adobe that is described as an experimental camera.

Project Indigo takes a different approach to computational photography. It underexposes more than most, pulls in up to 32 frames, aligns and blends them. The idea is simple: keep your highlights from blowing out, clean up the shadows, and walk away with a more balanced shot.

But you need patience.

There's a delay in start-up. And when you press the shutter, it's not instant. There's a pause while it works through those frames. A few seconds later, the result is less noise, better highlight control, and more detail in tricky light.

The other thing Indigo does differently? It doesn't lean hard on noise reduction. You keep more natural texture, even if that means leaving a trace of grain.

You can shoot JPEG or RAW, and both benefit from Indigo's multi-frame magic. That's a rare trick—most cameras that do burst blending only give you a JPEG at the end.\

Indigo's super-resolution works—zoom past 2x on the main lens (10x on the telephoto) and blends a burst of frames for more detail than a straight digital crop. In good light, it's solid.

Indigo's super-resolution works—zoom past 2x on the main lens (10x on the telephoto) and blends a burst of frames for more detail than a straight digital crop. In good light, it's solid.

But here's the thing: you can get close to the same result another way. Shoot a 48 MP ProRAW with the iPhone's native camera, then run it through Photomator's Super Resolution. You get a high-res file with plenty of latitude, works in low light, saves swapping apps.

It's especially handy when you remember the 5x telephoto is only 12 MP. Crop a 48 MP main lens ProRAW, Super-Res it, and you can match or beat what Indigo gives you.

Indigo shines when you can slow down. Landscapes. Architecture. Scenes that wait for you.

Indigo shines when you can slow down. Landscapes. Architecture. Scenes that wait for you.

It's less at home in the chaos.

Leica LUX

The Leica name carries weight — history, status, craftsmanship. More than just a camera brand, it's a cultural symbol. A century in the business. Photographers talk about them in reverent tones. The prices match the reputation: an M11 body is over eight grand, and you're close to fifteen once you've added a lens.

Not my world.

Now they've brought that red-dot swagger to the iPhone with Leica Lux. £6.99 a month or £69.99 a year unlocks the Pro features — manual controls, Leica film simulations, and stills that look less processed than Apple's own.

The app is clean and unfussy in keeping with the brand. The main attraction is the Leica Looks. Essentially presets, but very well executed, with Leica's colour science built in. They give your shots character without pushing them too far.

But let's be clear, seventy pounds a year doesn't buy you a Leica. It buys you the idea of a Leica. It runs on an iPhone, through iPhone lenses. No hand-built body. No precision-ground glass. No rangefinder magic. Just an app with a famous name, some well-made presets, and an interface designed to feel Leica-like.

Come to it with the right expectations, and you can make some nice images.

A taste of the brand, without the thing the brand is built on.

A taste of the brand, without the thing the brand is built on.

Summary

Ultimately, all three apps, and maybe the grip's shutter lag, were up against the same enemy: heat. Florida heat, well above Apple's own limits. Most of the time, I was staring at a screen so dim it was practically blank. No way I'm fiddling with manual settings, squinting at focus-peaking lines I can barely see.

Florida runs hot around the clock in July. Sun drops, temps don't. Midnight in Miami can feel like standing under a hairdryer. Pre-dawn in the Keys, air thick, streets still radiating yesterday's heat.

I was shooting on an iPhone 16 Pro Max. Apple says the iPhone's happy up to 35 °C (95 °F) ambient. Out here, hot tarmac, humidity, and a phone working hard push the internals well past 40 °C. It doesn't matter if it's 2 p.m. in Fort Myers Beach or 6 a.m. on Collins Avenue — the heat never leaves.

I got used to ducking into stores, hotel lobbies, bars — anywhere with AC, just to cool the phone down.

Android makers like Samsung, Google, and Xiaomi have the same issue — users in hot climates often report dimmed screens, reduced performance, or camera shutdown warnings during Hugh temperatures.

The difference is that Apple is conservative with thermal management. Screens dim and features throttle earlier than some Androids to protect components, which can make it feel like the iPhone overheats “more” even if other phones are just as hot but don’t warn as aggressively.

The challenge isn't finding the perfect app or accessory to take the shot; it's keeping the phone alive long enough to take it. Better to point and shoot, trusting Apple's built-in tech to get the job done. Let the tech do its thing so you can keep your head in the scene, not buried in settings.